Who doesn’t like a good night’s sleep? Not only does it feel good, but it has many beneficial properties as well. Sleep has various effects on our hormonal system. For instance, it directly affects our growth hormone, as it’s released at the end of the first part of deep slow-wave sleep. Sleep patterns also change during our life span. Not only that but the total amount of sleep also changes with age. It’s generally accepted that it’s okay to sleep between 6-10 hours a day. On the other hand, having less sleep that can lead to depression and anxiety. Chronobiology applied to sleep medicine has advanced a lot in recent years and has many interesting options to offer.

Want to learn more? Keep reading the article by Dr. Jean-Yves Sovilla.

Using time and light to treat sleep disorders:

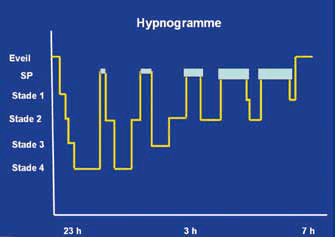

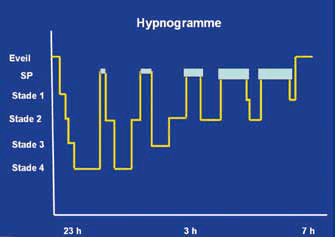

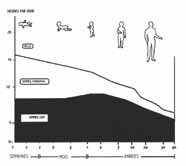

The universality of sleep: all living beings go through cycles of rest and activity. In animals with brains evolved enough to show fluctuations in their electrical activity, i.e. mammals and birds, in particular, we always find sleep comprising either phases of slowed cortical activity (slow-wave sleep) or a phase during which there is the activation of the cerebral cortex but paralysis of the muscles (paradoxical sleep). This sleep is organized in cycles that alternate between slow-wave sleep and REM sleep. Normal human sleep consists of four to five such cycles, each lasting between 90 minutes and one hour. (fig.1)

Among the many functions of sleep, one of the most basic is an adaptation to the living environment. Indeed, an animal can be adapted either to live during the night (nocturnal animal) or during the day (diurnal animal). It is interesting for the animal to take shelter during the period for which it is not equipped, i.e. a diurnal animal will sleep at night and a nocturnal animal during the day.

Sleep regulation system

Because of the specialization of living beings according to the presence or absence of light, sleep is regulated primarily by light. In the retina, there are special cells that are particularly sensitive to blue light, which is projected directly into the eye.

On the “internal clock”: the suprachiasmatic nucleus which is located in the central and lower part of the brain called the hypothalamus. This nucleus has the particularity of a very regular activity comparable to that of a clock. It sends information to the systems that regulate wakefulness and sleep. It is also the regulator of a hormone that is important for maintaining the sleep-wake rhythm in relation to the light-dark cycle: melatonin. (fig. 2)

The hormonal system is under the control of the lower part of the brain called the hypothalamus to which the pituitary gland is attached. This gland emits hormones that regulate other hormones. As a rule, this hormonal system is largely regulated by the internal clock system and by sleep. For example, one of the most important hormones for maintaining a healthy body, the growth hormone, is released at the end of the first part of deep slow-wave sleep, provided that we sleep at the time our internal clock tells us to go to sleep. This hormone regulates the repair of cells by activating protein synthesis capacities. If it allows growth in children, it is then part of the mechanisms that allow the regeneration of cells, which is why cell regeneration is much more present during sleep than during the day before. On the other hand, if we fall asleep at a different time from that given by the internal clock, especially if we go to bed late, the growth hormone is released in smaller quantities or not at all. This can be harmful or even fatal in the long term. For example, night workers or those doing shift work (3 shifts) have a high risk of developing cancer (grade 2 on the WHO scale of 5).

Other hormones, especially sex hormones, are also released in a sleep-related period at the end of the night, which may explain why men’s libido may be highest in the morning.

The chronotype

In humans, we can distinguish characteristics in relation to this regulation system: the chronotype. There are people who tend to sleep early and get up early, we call them the morning chronotype. On the contrary, some people are much more efficient in the evening and like to go to bed late and get up late, they are called the evening chronotype. Other people have an undifferentiated chronotype and adapt to circumstances. The morning chronotype is the most resistant to change.

Age-related changes in sleep patterns.

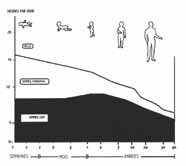

The normal time of falling asleep varies with age. As a child, he will need to go to bed very early, but from adolescence onwards, there is a marked shift in the time of falling asleep, which is often close to 24 hours, and then over the years the time of the need to fall asleep will move backward, sometimes returning in the early evening. On the other hand, the total amount of sleep needed to feel well varies with age, so that a newborn baby may need to sleep for 16 hours out of 24, but then the amount of sleep will decrease to a median of 8 hours per 24 hours in adults. (fig. 2)

How many hours of sleep do we need?

When a biological quantity is measured, the Gauss curve (bell curve) is almost always found. In the context of sleep, this curve indicates that normal sleep duration ranges from a theoretical minimum of six hours per 24 hours to a theoretical maximum of 10 hours per 24 hours. Any sleep duration above or below these limits will be considered pathological, but only if this trend is stable.

Constraints on sleep in modern life

If in the wild animal (and the human being before electricity!) sleep is mainly regulated by the passage from day to night or its opposite, in the human being social constraints (working hours for example) have an important influence which comes in addition to but does not necessarily replace the natural constraints of the functioning of our internal clock. In our 21st century life, another element has come to strongly disturb the natural course of the sleep-wake cycles: leisure activities that can be endless: television and other devices using luminous screens (Smartphone, tablet), the possibility of going out at night, etc.

Sleep is able to adapt to these constraints because it has the possibility to create a “sleep debt” i.e. to sleep less than necessary (create its debt) and then to pay it back when possible (sleep longer during the weekend or holidays).

What happens if you don’t meet your daily sleep requirement?

A very interesting experiment was carried out to find out what happens if you stay in bed for a long period of time. Volunteers, students, were asked to spend 14 hours a day in a sleep laboratory in a bed in the dark. Like all young people, these volunteers were in sleep deprivation and so for the first few nights they had a very long and compact sleep. As the experiment went on, the sleep became more and more fragmented, i.e. there was more and more wakefulness during the recording period and the sleep cycles became totally irregular. This leads to a feeling of tiredness that only increased during the three months of the experiment.

Numerous measurements were carried out to determine what would happen if, in contrast to the previous experiment, one was deprived of sleep for a long time. This was also done mainly in young and healthy people. Without wishing to be exhaustive, the study that measured the average blood pressure and the so-called insulin resistance, which is an abnormality preceding diabetes, is of particular interest: it was enough to reduce the total sleep time permanently to see the first biological signs of insulin resistance appear. Several studies have followed patients for years on a psychological level. For example, a cohort of young people was followed in Zürich to see what factors predisposed them to depression, a study that showed that one of the most serious risk factors for depression was chronic insomnia.

Means of investigating the functioning of the internal clock

These are simple means: the sleep diary, which is a small graph filled in every day by the person being investigated, and also the use of a small device that records movements, and possibly also ambient light, and which is called an altimeter. This makes it possible to study the evolution of a person’s sleep and physical activity easily and over a long period. Recently, this type of device is commonly used by young people, often in connection with either their smartphone or a computer. Only if there is a suspicion of something more serious than sleep hygiene disorders, an examination such as ambulatory polygraphy (recording of breathing and heart rate during sleep) or polysomnography (recording of sleep and all physiological criteria in a sleep laboratory under constant supervision) will be performed.

Some concrete examples of sleep disorders treated by chronobiology

First example: THE SLEEP OF THE TEENAGER.

A is a young man in high school who has seen his school results fall since the end of the summer holidays. In fact, he can no longer get up in the morning at the usual time, which means that he does not go to school several days a month or arrives late. Having to travel by public transport to school, he sometimes falls asleep in the morning and wakes up at the bus terminal. In class, he has concentration problems, and especially in the early afternoon he sometimes falls asleep. In the evening he does not sleep, stays in front of his computer watching films in his room, and then goes to bed with his smartphone on which he sends messages until two in the morning. At weekends he goes to bed at six in the morning and sleeps until around one o’clock in the afternoon with a quiet sleep.

Assessment of the situation: This is typically a phase delay syndrome. His sleep has shifted to the morning and he can no longer sleep at the usual time. This is due to the fact that he uses blue light screens which will give his internal clock system the message that evening is actually day. It is very likely that his sleep is normal as such but that it occurs at an inappropriate time for social obligations.

Treatment: sleep must be adjusted to the standard time so that the child can go to bed and sleep at around 10 p.m. and thus get eight hours of sleep.

To do this, the child is asked to get up at a fixed time, often with the help of the parents, around 6.30 a.m. to stand for half an hour in front of a powerful lamp which emits 10,000 lux of light, light which is devoid of toxic infrared and ultraviolet radiation, and which will give the child’s clock system the indication that it is morning. At the same time, he will be given melatonin in the evening or late afternoon to give his brain the indication that it is evening. He will be forbidden to look at screens and generally to be in places where the light is intense. In principle, within one to two weeks, sometimes within a few days, the situation becomes normal and the patient can resume normal activities.

Second example: A COMPLAINT OF INSOMNIA.

B is a 70-year-old patient who complains of not sleeping from three in the morning. His doctor prescribed a sedative to be taken at bedtime but this did not change his difficulty in staying asleep until the morning. When asked about his sleeping habits and feelings, we learn that he starts to feel sleepy at 7 pm, that he frequently falls asleep in front of the TV news and wakes up around 10 pm, do his ablutions, and goes to bed, often having difficulty falling asleep despite taking the sedative, and that he wakes up at 3 am tired but unable to sleep. As he is tired, he often takes naps that can exceed one hour in the early afternoon. He feels unwell, sluggish, have problems with concentration and memory, and has had several falls.

Assessment of the situation: this is typically a phase advance syndrome. It is the reverse of the previous situation, i.e. the chronobiological rhythm has shifted the need for sleep to the evening and when the patient has had enough sleep, he or she naturally wakes up. This is a frequent characteristic in the elderly and can be aggravated by a home-based activity (not being exposed to sunlight during the day, for example) or by a pathology that is very common at this age: cataracts, which particularly reduce the passage of blue light and therefore the setting of the clock.

Treatment: the previous procedure is reversed: the patient is given light therapy in the evening by spending half an hour in front of the 10,000 lux lamp at around 8 pm. In principle, this light is enough to delay sleep so that the patient can go to bed later, and for at least two weeks he will be given melatonin in the morning to make the brain believe that the evening is later than it actually is. In principle, in one or two weeks the problem is solved, sleep occurs again at the end of the evening, there is no more abnormal awakening during the night and the capacities of memory and concentration improve, even the balance improves, especially if the sedatives are stopped.

Example 3: PERTURBED SLEEP

C retired six months ago. Previously it was necessary for him to get up at around six o’clock in the morning to get to work on time. Since this necessity has disappeared, C now takes advantage of his situation to sleep in: no more waking up. Very often he also takes advantage of going to bed later to watch interesting programs on television at the end of the day and gets up between eight and nine o’clock. Whereas he used to have no sleeping problems, he starts waking up more and more often during the night to urinate but cannot go back to sleep as before. He gets upset in bed and feels more and more tired. He goes to see his doctor who gives him a sedative. For a while the situation becomes normal, i.e. the periods of wakefulness become rarer and shorter, but after a few weeks the situation returns to the previous one.

Assessment of the situation: C probably has a normal sleep requirement of around seven to eight hours per day. By regularly spending more than eight or even nine hours a day in bed, his sleep has become diluted and unstable, as in the experience described above.

Treatment: simply reduce the time spent in bed by resuming an alarm clock after seven and eight hours of sleep.

Can chronobiology treat all sleep disorders? Of course not, the situations mentioned above presuppose that the sleep of these people is intrinsically normal. It is therefore necessary to assess whether there is a specific sleep pathology that requires an instrumental evaluation or whether there is no necessary examination at first sight, which could be proposed if the chronobiological treatment fails.